Hood is a Sacramento County testament to farming know-how and the migrant dream – and an obstacle to the state’s most powerful lobbyists

There’s a final light on the cherry orchards, sundown brightening bricks on Hood’s River Road Exchange building as it touches the relic’s sloped hump and frosted sugar-cube windows from another era. Voices are laughing past the structure’s mammoth Art Deco façade. The evening sharpens its palms, their leaves fanning ahead of the battered tin roof to a packing shed from the Great Depression. A few women in evening gowns stop to observe it – a kind of canary-yellow Noah’s Arch steadily suspended over the Sacramento River. They can see how it’s hunching on old wood poles that drill down where twilight meets a calm crystal mirage on the current.

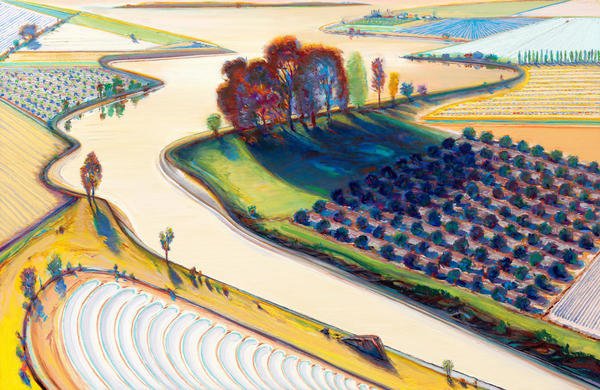

Sunsets like this were common when the late artist Wayne Thiebaud lived in Hood in the 1960s and 70s. Thiebaud’s paintbrush captured this corner of the North Delta in muted and delicate colors, his visions settling into cotton candy dreams of the how the bending river kissed its fields and the windbreak trees splashed fading shadows on fruit groves.

It still looks that way here.

Brett Hall Jones, whose late mother, the photographer Barbara Hall, grew up in the same ornate Victorian that Thiebaud painted in when Hood was his home, says the waterway flowing by that ranch to the center of town represents a generational convergence for artists, fieldworkers and homesteaders.

“It’s all of California history,” Jones reflects. “It’s a stunning place – incredibly beautiful.”

Tonight, a crowd of visitors in tuxedoes and gowns are glimpsing the agricultural part of Hood’s legacy. That’s because the River Road Exchange building – a place where Stillwater Orchards once moved fruit from steamer boats onto boxcars that were lurching up the wharf’s train spur – is now the Willow Ballroom, an events venue that combines rustic nuances with Golden State grace. Inside, there are drapes falling over time-tempered columns. There’s dripping wax torches and shabby chic candelabrums throwing light on the spacious, homespun floorplan. With every gala held here, the Willow Ballroom becomes a better-known escape for urbanites seeking some country elegance only 15 minutes by car from Sacramento’s border. That also means the ballroom has become the main ambassador introducing Northern Californians to this tiny, highly threatened town of Hood.

Threatened because of state officials and the financial muscle of special interest groups in Southern California.

But what exactly is Hood? Is it just the lightly populated remnant of a settlement from 1860? Little more than a long-ago junction? Viewed through that lens, choking the town’s commerce and livability to death with up to two decades of intense, nonstop construction– along with the government commandeering much of its land through widespread eminent domain seizures – might seem like a fair trade to build the state’s controversial Delta tunnel. At least, it might to advocates who argue the project will provide more water security to far-off, billion-dollar agribusinesses.

But to the families who live in Hood, the town represents something much different: It signals a multicultural testament to the migrant farming story of California. Beginning in World War II, a cadre of Mexican-American and Spanish-descended families re-settled in Hood in order to keep the Delta’s bountiful bread basket flourishing as local men fought a nightmare on two fronts. These industrious newcomers worked Hood’s Bartlett pear orchards so well that the Delta got more involved with the Bracero Program, which allowed Mexican nationals to legally become Americans as they took up the area’s ranch and fieldwork. Over time, those families who came between the attack on Pearl Harbor and onset of the Vietnam War made themselves into an enduring part of Hood’s DNA. According to the 2019 census data, nearly 70% of the town’s 313 residents are Hispanic; and people around Hood can usually break down how most of the community descends from those original families who saved Delta farming during the nation’s darkest hour.

They were personalities who largely stayed in Hood, allowing it to remain a vibrant part of Sacramento County’s $455 million annual agricultural economy by growing cherries, almonds and wine grapes. But their role in California’s ag accomplishments could soon be erased, along with those of the Portuguese, Dutch, Chinese and Japanese farmers who worked the Delta before them.

In recent years, the official environmental documents for the California Department of Water Resources’ proposed Delta conveyance system – first known as “twin tunnels,” now envisioned as a large single tunnel – have predicted an unimaginable future to many living in the estuary from Clarksburg to Isleton. They estimate 14 to 20 years of relentless, ground-punishing construction along the old levee roads and nearby fields – the residents and business owners who stay having to live with stadium-lit excavation, deep dredging, steel pile-driving, ground well-draining and the demolition of historic homes. They’ll also have to try to coexist with constant big-rig traffic that could make it impossible for businesses to stay open and farmers to get their harvests to market. DWR’s own documents show that, once the tunnel is finished, swaths of that bucolic beauty that Wayne Thiebaud framed with his paint brush will be transformed into a steel-and-concrete industrial no man’s land. The state’s maps, models and schematics don’t lie: The character of North Delta running through Sacramento, Yolo and San Joaquin counties would be irreparably altered. The word that people who live here would use, is “desecrated.”

The town of Hood stands at ground zero.

Just a few weeks before the pandemic hit, town folk got an early shock when DWR officials unveiled the “down-sized” version of the tunnel that Gov. Gavin Newsom had ordered then to recalibrate. While the newer conveyance system changed from dual tunnels to one, the plan still called for two 1,000-foot-long metallic intakes along a six-mile stretch of the Sacramento River, one gargantuan station on each side of Hood. Additionally, the plan called for Hood to be caught between several long-term construction yards and geotechnical exploration zones.

Tom Keeling, an attorney who’s spent more than a decade representing local counties and Delta farmers on eminent domain issues around the tunnel, said more than 125 property owners have already battled DWR all the way to the California Supreme Court over access to, and the future of, their lands. The state’s latest models indicate the next stage of that fight will happen on parcels to the immediate north and south of Hood along Highway 160. The seizures could even extend into the town itself. The full amount of forced access and land acquisition that DWR will need for the tunnel’s enormous intakes is a figure the department still hasn’t revealed. But, based on what he already knows of the DWR and its project, Keeling told SN&R that the intakes will spell “an intense need for private property.”

The Whaley family, who restored Hood’s landmark fruit exchange with the grandeur of the Willow Ballroom – and who tonight are hosting a hundred happy Sacramentans under fairy lights and evening clouds over the river – knows better than most Californians that the state is fully capable of casting that large of an eminent domain net. Their family has lived through two seizures like it before, first when the federal government demanded the abandonment, takeover and ultimate destruction of the town of Port Chicago along Suisun Bay west of the Delta in 1965; and then when DWR legally took control of 500 acres of the Whaley family’s property on Winter Island in the Delta in 2016. For the Whaleys, there’s no question that state department heads working under Newsom would do it.

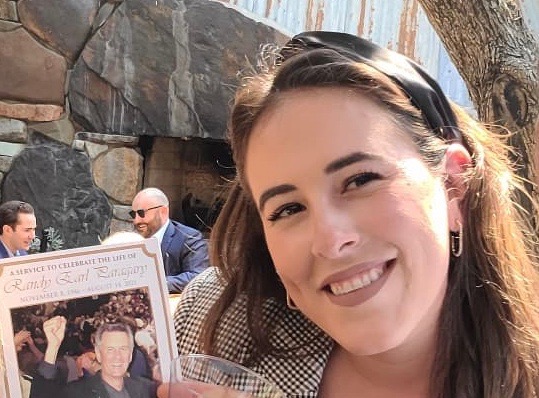

At the moment, Angelica Whaley, the youngest member of the family, is dressed in sleek black attire as she escorts guests around the wood columns and dapper bouquets of the ballroom. Understanding Hood’s current peril, Angelica reluctantly agreed to join a Stakeholder Engagement Committee that the state put together while designing its latest version of the tunnel. The committee was billed as a way to give Delta residents and indigenous tribes up river a voice as the culturally impactful project moved ahead. Angelica soon decided the committee was anything but: She watched in dismay as DWR proceeded full-steam ahead with the tunnel even after the state’s own independent team of engineers released an analysis calling it “logistically impractical”; she scratched her head as officials appointed by the state pressured her committee to work through the scariest part of the pandemic and then got caught misleading a commission about it; she was startled by an SN&R investigation that revealed the state’s top official for the tunnel was being paid twice as much as the governor to steer the project to completion; and she was appalled when DWR filed a lawsuit that sought to block every Californian from contesting how it will finance the tunnel’s $22 billion price tag.

In September 2021, Angelica and several other members of the Stakeholder Engagement Committee officially resigned, describing it as a lip service illusion intended to provide political cover for greenlighting the tunnel quicker. Now, Angelica is waiting. She’s waiting to see whether or not – if the Newsom administration continues to ignore independent scientists and environmental groups about the tunnel potentially collapsing the Delta’s wildlife habitat – a slew of court battles might still somehow save this farming community she’s come to love.

“We were basically asked not to speak. We were silenced, honestly,” Angelica says of the committee. “How do you sleep at night, knowing that you’re literally destroying the ecosystem of the Delta? In a lot of institutional government projects like this, they do this ‘outreach’ to make themselves feel better and sleep at night. They tell themselves, ‘Oh, well, we’re engaging the community, so what we’re about to do has to be OK.’ Well, it’s not OK. Not in this case.”

After a pause, she adds, “Whenever we’d press them, they’d say that this is all hypothetical. It doesn’t feel hypothetical. This is our life – this is our home.”

Scenes from sundown

Another night with the river moon.

A car drifts down Highway 160 where gnarled oaks along the Sacramento reach into contours of moonlight falling over the channel. For an instant, headlights break the sky’s pale spell of cobalt blending with waves that slip by vines and wild oats spread across the shore. When there are no lights, it’s a perfect picture of stillness and breezes. The levee is pocked with old farming mansions that seem to lean back into this chroma of lunar color, with their splintered wood columns and threadbare balconies struck against a fading spectral pearl on the horizon. People here think that you can’t know the river moon from a car window. They say you won’t catch its rural witchery with the technology on your cell phone. Some living in the estuary claim you need to sense the silence, and hear the night owls, and watch the subtle movements of the tide, to really understand it. But known or unknown, the river moon is out tonight – in full satin force over the dipping berms and sunken orchards.

Down the road, lamps are burning against the crimson stone of what was once Hood’s mercantile and supply store. Like the Willow Ballroom, this hardened Delta survivor has been gradually restored into a new center of life, with its ragtag river charm conjuring an atmosphere somewhere between hayseed style and working-class refinement. The bustling restaurant inside is called Hood Ranch Kitchen; and sitting with elbows on its bar and a ballcap turned backwards is Mario Moreno, a life-long Hood resident who many call the unofficial mayor of the town. Mario has a big voice and booming smile and appears to generate a mini-party everywhere he goes. At the moment, he’s cutting and carving his way through a huge slab of dripping, ruby-centered prime rib while sitting next to his 29-year-old son, Marcus.

Mario’s years growing up in Hood include memories of collecting crawdads in the irrigation ditches, fishing under blue oaks that draped the river, watching almond blossoms explode in the warmer season and tracking flocks of geese under the clouds while he rode his bike for miles on the levee road to Sutter Island. In 1978, when Mario was 13, the very last train from Southern Pacific snorted its way up the spur to Hood’s aging wharf. That meant the town was no longer a commerce junction. For Mario, it would still remain a place where every kid was welcomed into every living room, as if Hood itself was one extended family.

Seven years ago, Mario retired as an energy advisor from SMUD. Marcus, on the other hand, has graduated from University of the Pacific with a master’s degree in civil engineering. When Mario thinks about his family’s journey within the California story, coming to Hood as farm laborers in the 1940s to discover a quiet, stable way of life that allowed him to have a middle-class career – and allowed his son to strive for greater professional ambitions – he sees a microcosm of what the town has meant to so many families connected with it. That trajectory started when a number Mexican-American and Spanish-descended households came to Hood during the labor shortages of World War II. Mario knows those surnames well: the Montano family, the Ortiz family, the Lujan family, the Chacon family – the Moreno family. Most of these families had first settled in Colorado before later coming out west to Hood. At some point, the Lucero and Dominguez families arrived to help build the town, too.

Mario says most of these hardworking field clans had their roots in Mexico’s Michoacan and Jalisco regions. Some of their third and fourth generations have been forging a new path, graduating from institutions such as McGeorge School of Law or landing jobs all the way at the state capital. It’s this cultural evolution that sprouted from Hood’s history and way of life, allowing younger people like Marcus to become an engineer, that sometimes chokes Mario up with unexpected emotion.

“These families continue to live in this town to this very day,” Mario mutters, fighting back tears. “And they’ve contributed to building their local economy by working, and they contributed to raising families, to the point where some of their grandkids have achieved all these things. It’s that typical migrant story that resonates. It’s people who have wanted to better their lives … When I come at it that way, it’s just, ‘Wow, who would have thought?’”

On this night under the river moon, Mario and his son are laughing as they chat with farmers and town folk around the bar. Like most regulars at Hood Kitchen, they’re big fans of its chef, Emiliano Zappata, a calm, soft-spoken man who has an easy smile when he’s greeting regulars. Between mastering Omaha Ribeyes and grilling up shrimp scampi in butter, garlic and white wine, Zappata sometimes finds moments to step out into the dining room to make sure everyone is enjoying their dishes. Lately, even with the supply chain chaos, Zappata has managed to continue getting ahold of top-quality beef cuts, enough to drive demand for Hood Ranch’s wildly popular prime rib Thursdays into an additional Friday night affair.

As Mario and Marcus are digging into Zappata’s gorgeously marbled prime rib, one of the restaurant’s owners, Ben White, is also making the rounds with locals as the night darkens. Ben and his wife Kim took over Hood Ranch Kitchen two years ago and immediately established a reputation for treating employees like family. Many in Hood feel they’ve shown a similar commitment to the town, with Ben serving as one of the North Delta’s volunteer firefighters. The couple’s bar manager, Jamie Chapin, lives just up the road from Hood Kitchen. She’s come to see the hamlet as a genuinely unique place.

“What I love about it, personally, is that there is a really big sense of community here,” Chapin says. “Even though I’m relatively new, I can’t drive down the street without six different people waving at me. I feel safe because I know that everyone in town is looking out for me. There’s just a true sense of togetherness.”

That togetherness can be glimpsed in the lawn signs all around Hood that read, “No tunnel is worth our town.”

‘Rosebud’

A fishing boat skims down the Sacramento River, drawing its wake through reflections of trees conjured by a bright open sky. Just over the levee from it, tree branches sway in slight movements above a pink, three-story Italianate manor house. The structure is a decorative edifice of arched windows, soffited eaves, gabled touches and fluted Corinthian columns. Built in 1877, this study of hipped roofs and paneled friezes is known as Rosebud Ranch.

The San Francisco photographer Barbara Hall’s very first memory was of this place. She lived on the ranch’s property with her mother, Harriet, who every night would go down the bank to swim under the river moon. Through the fog of time, Hall could picture the drip-drop of water hitting worn floorboards as it came off Harriet’s locks whenever she’d return. Hall was the great-granddaughter of state senator William Johnstone. A political force in Sacramento agriculture, Johnstone convinced the same architect who’d designed the California Governor’s mansion to dream up this eye-catching estate along the water. When Hall was 5 years old, Harriet suddenly died. She was forced to live inside Rosebud’s looming house while being raised by Johnstone’s two prim, reclusive and aging daughters, whom Hall would always remember as holdover Victorian ladies. Much later, in the 1970s, when Hall’s photography was being featured in gallery shows around the Bay Area, this native daughter of Hood could still picture fieldworkers and ranch hands gathering at the porch of the big house; and she could envision going down to meet boats along Rosebud’s docks with large bundles of cherries; and she could recall the starving, river-wanders of the Depression knocking at the backdoor; and she could see and smell the wonders of a Chinese immigrant camp on the edge of the property, where a big cauldron of cooking food was constantly bubbling over an open fire.

Hall may have photographed the world’s far-off places, and made portraits of the best-known writers and poets of the West, but her memories of growing up in Hood remained part of her identity as a California artist.

“She loved everything about growing up at Rosebud Ranch, except her broken heart over her mother,” says daughter Brett Hall Jones. “She had clear and loving memories of the place, and in her later years, not long before she passed, those memories really just started pouring out.”

In 1968, Wayne Thiebaud bought Rosebud Ranch from Barbara Hall’s brother, Jack. Thiebuad had already been painting for a decade and had a solo show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Thiebaud gained a reputation within the Pop Art movement with soft paintings of everyday American stand-ins, confections and desserts from lemon meringue pies to cherry-topped ice cream sundaes. Over the decades, the versatility of his brush outgrew the Pop Art designation. Thiebaud eventually pushed himself toward imaginative figure studies and intriguing illustrations of landscapes. At least four of the landscapes were centered on the North Delta and its farms and fields around Hood.

Mimi Miller, wife of Thiebaud’s close friend, the late Sacramento mayor Burnett Miller, was close with the famous artist back when he lived at Rosebud Ranch. She says that, for a time, the area around Hood was a constant part of Thiebaud’s creative life.

“He painted a lot when he was out there,” Mimi recalls. “His signature had a rose in it, and I think that would have come from Rosebud Ranch.”

Thiebuad’s paintings are now featured in some of the most prestigious art galleries in the United States. He passed away, in Sacramento, in December of 2021. Barbara Hall had passed away in 2018.

Rosebud Ranch is officially on the National Register of Historic Places. That’s because of its place in Thiebaud’s career, as well as the fact that it was designed by pathfinding California architect Nathaniel Goodell. Rosebud Ranch is also directly in the crosshairs of the Delta tunnel. Specifically, DWR’s models show that one of the project’s Deathstar-like 1,000-foot steel-and-concrete intakes would be built almost immediately in front of the lauded old house.

“DWR has never reached out to us, but we have attended countless public hearings over the past 10 years,” explains Cheryl Cox, who now owns Rosebud Ranch with her husband, John. “Each comment and every letter has fallen on deaf ears. … Their plan is to take our property by eminent domain and tear it down. They intend to ignore the historical significance of Rosebud. … Our home would be demolished to make room for the project’s access road that will divert Hwy 160 away from the river.”

With indigenous tribes, fishing associations, environmental and conservation groups and a great many Southern California ratepayers opposing the tunnel, who exactly are the project’s main supporters? Within the public-private sector, the driving force has been the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, or MWD, the largest water contractor in the state. MWD has spent millions helping finance the Joint Powers Authority that’s tasked with designing the tunnel and getting it approved. In December of 2020, its board of directors ignored hours of public outcry from customers and voted to spend another $58 million to help continue funding the tunnel’s design.

In the corporate world, the tunnel’s big champions have been Lynda and Steward Resnick, billionaire almond and pistachio barons known for their philanthropy, including giving hundreds of millions to California Institute of Technology and bankrolling PBS endeavors like the films of Ken Burns. The Resnicks have donated more than $366,800 directly to Gavin Newsom’s campaign and, last year, officially underwrote the effort to prevent the governor from being recalled from office.

Newsom’s team did not respond to an interview request for this story. When the governor downsized the earlier two-tunnel version of the project, he said it was because of water and environmental concerns, adding, “I don’t support the twin tunnels. We can, however, built on the important work that’s already been done.” Since DWR revealed that Newsom’s newer version is arguably just as destructive to the North Delta – particularly to Hood – as the earlier version, Newsom has made few public comments on the matter.

A draft of DWR’s latest environmental impact report for the tunnel is expected to be released in mid-2022, followed by a public comment period. Once that EIR is completed, there is a high likelihood that numerous county governments, Delta farmers, environmental groups – and the California fishing industry – will all immediately sue to stop the project. At that point, the fate of Hood and its surrounding communities could end up in the hands of a judge. Again.

“It would be an outrage, and the saddest thing in the world, if Rosebud Ranch and the town of Hood were lost,” says Jones. “I think it would be the erasure of a place.”

For Angelica Whaley, the thousands of new people who are discovering Hood through her ballroom, or through the Hood Ranch Kitchen, might offer a ray of hope when it comes to more political support.

“People are just amazed that such an incredible place exists,” Angelica notes. “They just want to know all about what’s on the river, because there’s a yearning for that – to get back to their roots and be somewhere that’s not on the grid. And they love that it’s a beautiful place that’s just outside Sacramento. That’s what the Delta is.”

Recalling she grew up just a few miles down the river in Courtland, she adds, “the Delta is a place that people come back to: People from here know the joy of having a childhood playing in the pear orchards, and being close enough to walk to your friends and neighbors. There’s something to be said for all that.”

Mario Moreno agrees. As someone who’ll go to the dirt to sing Hood’s praises, he thinks that newer visitors to the town will find their real treasure in conversations and connections with locals.

“The town’s story just represents those things we all, as Americans, value,” Mario reflects. “We take pride in our community and hopefully that shows in our hospitality and our friendships.”

Odd one of the oldest businesses in Hood wasn’t mentioned in the article again from SNR The Antique shop is still going strong . Just saying huge miss lol

The Delta is a precious biosphere that must be protected from pillage and plunder.

Scott thanks for hypnotizing me with this article.I’ve read it twice now. So many families that have been here forever and so much history that could be erased like no big deal, I don’t live there not my problem. The part about the guy making twice as much as the current gov.his last name was Brown. It’s all so shady .

Thanks Rvbridgeman

Ps looking forward to the next story !

Thank you Scott for this outstanding piece of investigative journalism and demonstration of compassion and love for our heritage, communities and quality of life. Please, if you read this article, write to Newsom and let him know you oppose this boondoggle. It will go on for 20 years and the impacts will last forever. It will end up costing $100 billion dollars and will also cost us not only our heritage but the fragile ecosystem that is the California Delta. Please help save the Delta.